|

|

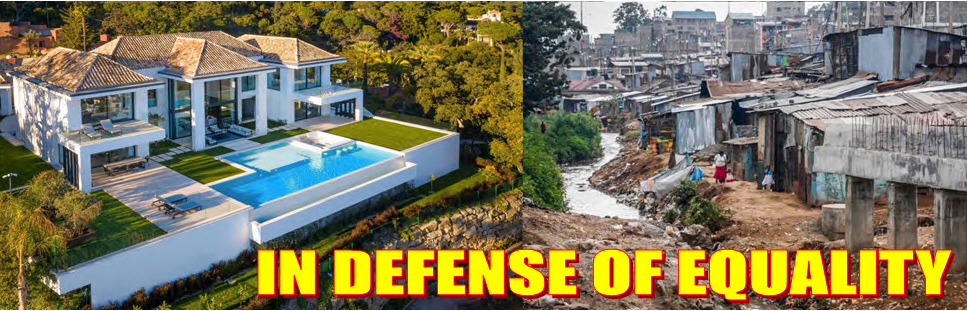

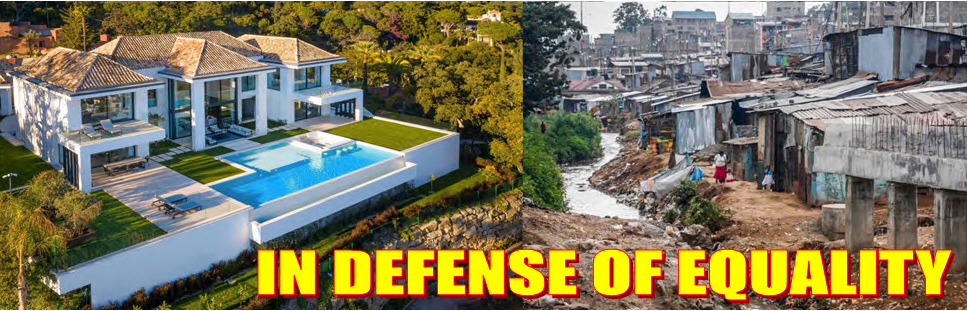

We live in a time where it is endlessly repeated that private property is the foundation of freedom, prosperity, and social order. It is said that defending it without restrictions is equivalent to defending progress. But this discourse, which sounds good in headlines, hides a deep contradiction: what is the point of defending property as an absolute right if thousands of people don’t even have access to a decent roof over their heads?

The clearest example can be found in Madrid. In La Cañada Real, hundreds of families have lived for years in neglected conditions, without guaranteed access to basic services such as electricity. Many of its residents have been ignored or criminalized, while the conflict over land ownership—between regional governments, local councils, and private owners—drags on indefinitely. There is much talk about the "right to property," but what about the right to live with dignity?

This is not an isolated case. It reflects how, in Spain and many other parts of the world, the defense of private property has been confused with the defense of the interests of the wealthiest. When it becomes taboo to talk about redistribution, when taxes on wealth or assets are demonized, what is really being protected is not freedom, but a profoundly unequal order.

In contrast, the state has an irreplaceable role: to guarantee rights for all, not just privileges for a few. There are things that individuals cannot solve on their own. Housing, education, healthcare, mobility, and energy cannot be left to the whims of the market or charity. Only strong public action, with redistributive policies and effective regulations, can correct structural inequalities.

And this is not just theory. One only has to look at the evolution of rental prices in cities like Barcelona or Madrid, where many neighborhoods have become targets of speculation by investment funds and large landlords. Meanwhile, thousands of people are unable to find affordable housing. Property cannot be just a tool for profitability. It must also serve a social function.

But whenever measures are proposed to correct these imbalances—such as capping abusive rent increases, taxing large landlords, or reclaiming vacant homes for public use—the same arguments arise: that freedom is under attack, that legal uncertainty is being created, that the economy is at risk. But what about the real insecurity of those who can't afford a home? What about the economy of those who can’t make it to the end of the month?

Inequality is not an abstract problem. It has faces, names, and addresses. It also has figures: in Spain, the richest 10% hold more than 50% of the country’s wealth. Can we truly talk about freedom when the starting point is so unequal?

That’s why it’s important to remember that equality doesn’t happen by inertia. It must be built. And only the state can guarantee it—by stepping in where the market fails, correcting the excesses of capital, and protecting those who have no voice in the major headlines.

Private property may be a legitimate right, but it cannot stand above the right to a dignified life. It cannot be used to exclude, to speculate, or to shield inherited privilege while denying opportunities to the majority. It cannot be an excuse for inaction.

Defending equality is not about going against anyone—it’s about standing up for everyone. It’s about ensuring that democracy is not just a façade, but a shared reality. And that requires political will, fiscal justice, and the courage to break away from narratives that disguise privilege as freedom. Because without equality, property is not freedom—it is domination. And without a state to prevent it, that domination becomes law.